Lorene Taurerewa and A Sensible World. An essay by Owen Davidson

The title of Lorene Taurerewa’s latest show, Sensible World, teases us with our misunderstanding. How can the world of these paintings make sense?

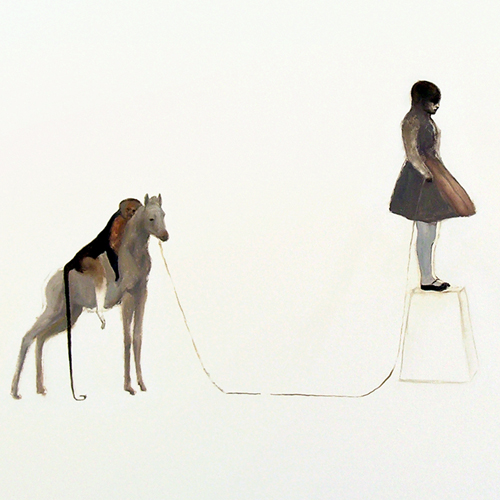

The wit of these paintings is in the tradition of Edward Lear’s nonsense verse, with surreal shifts in scale and role-reversals between human and animal. They also belong to the ancient tradition of Aesop; from the time we shared our world with the animals, lived in close relationship with them and studied their moods, thoughts and personalities, finding in them reflections of our own.

Children growing up with pet animals in the family back yard relate to them in deep ways. When you are the size of a child, adults are giants from another world: but pet animals are the same size as you: they are the same age as you in years; but become older, stronger, and wiser. For a child’s mind their pet animals enact the role of life more completely than do other humans, whose lives are fixed in place in the sequence of generations.

In these paintings the animals are the strong and intelligent ones, free to roam and express their immediate emotions about belonging to this world. But the human inhabitants of these worlds are kept in the middle distance, isolated between large volumes of space, beside them, behind them and in front of them. They are incomplete; suspended from becoming part of their world; clouded from action in the present by uncertainty, apprehension, and vulnerability.

In the small, simple ink drawings this effect is achieved by the mylar, whose translucency holds just enough light to suggest a deep world of space, the ink images suspended within. In the paintings it is the artist’s skilful use of colour temperature, value contrast and quality of line which conjure up the suggestion of un-traversable space in front of and behind the plane of the canvas.

The illusion of spatial depth is the most basic conceptual tool in the western, European, tradition of painting - Ms Taurerewa’s heritage in terms of her school of training. But in recent years she has been making a personal study of a different tradition, one which establishes itself on a quite different concept of space: and the influence of which is showing itself strongly in the paintings of this show. This is the eastern, or Chinese, tradition.

In Chinese painting the most fundamental concept is that of Void, or Emptiness. The ink marks that go down on the white paper are fullness “dropped in” to this emptiness; they need emptiness the way words need silence; the process through ink between brush and paper is the same as the flux between the empty and full states of nature; and these marks are simultaneous thoughts, meditations on nature’s truths, nature’s “way”.

This sense of purity and stillness of concentrated thought holds strong in Ms Taurerewa’s paintings. Her painting shows us the process of thought trying to find memory. Memory has been selective; editing out the background of what it chooses to find important. Trying to find memory, thought becomes focused and dense; emptying out the surrounding space. This is the natural way of thought, the paintings’ titles imply – they are lines, or fragments of lines, from theTao Te Ching, Lao-Tzu’s book of the Way of Nature.

The painting that is most evidently an image of the artist - a self portrait of a kind - is titled My Words Are Easy To Understand.

Memory does not make meanings as our conscious mind would. It has formed weird relationships, according to choices of emotion, instinct, and sensation. Therefore the meanings of memory are sensible, not comprehensible – they have to be sensed, not comprehended, to be understood. Understanding is something deeper, quieter and longer-lasting than rational comprehension: when the mind comprehends something it moves on to other matters; when it understands, it forms a lasting connection with a truth, and brings companionship to comfort the loneliness of the adult-child in the picture.

Owen Davidson 2008