From Impressions To Fossils: Matt Couper's Accumulating Signs. An essay by Anthony Morreale

We often imagine the artist as an exemplary figure of action. The artist is creation, the artist is the source, and above all the artist is an individual. In this configuration the artist opens up a gateway to a primeval force inside of her/himself and, through great effort, births some new and beautiful thing into the world. The artist, in his activity, is a medium between the world of things and the world of an amorphous and sometimes dangerous will. By this connection to the otherworldly, artworks are lent a magical quality, a certain glow– an aura like residue from an obscene and thrilling encounter. Perhaps this link between the artist and the shaman is telling.

Unlike this figure of the artist, the shaman, for all his/her artistry, is in contact with individuals. The shaman knows demons and spirits, the shaman has tamed them or befriended them, the shaman isn’t the source, the shaman isn’t the individual, the shaman, in her activity, is multiplied into a conference of testimonies. We can plainly see how the artist, like the shaman, is in contact with something alien, but how can we let this superimposition ricochet? How can we let the shaman in the artist gain prominence over artist in the shaman? In other words, who can make an artwork into a conference of testimonies? Or who can let the forms speak for themselves?

+++

I nominate Matt Couper. Admittedly, I would never have suspected such a man to hail from New Zealand (after all, aren’t there more sheep than people there?). New York City, Paris, somewhere like that seems more fitting. In fact, Matt seems even more unlikely a candidate upon meeting him. There is nothing stereotypically shamanic about him: he has no face paint or ridiculous jewelry, his fingernails are cut and he wasn’t wearing a robe or gourd, he didn’t even have a human skull handy (though I’d wager that he owns one). His style is so unpretentious, that I could hardly believe he was the source of all that magic clustered over the austere walls of the gallery. With a shaved head and warmly attentive eyes, he was all smiles and graciousness. Nothing about him betrayed that he was the author of this beautiful and gory cultural massacre.

Matt’s work speaks for itself, and it speaks like a Ouija board. This is not to say that there’s something evil in his work, and I think it would be offensively naïve to think along these lines. These paintings are in fact a struggle objectified, voices wrestling on the canvas before us. Unlike our imagined shaman, these aren’t the voices of the woods, the streams, or the faeries who monitor trespasses and social pollution, instead these are the voices proper to our moment, these are the voices familiar to us, murmuring softly through our deep history and shrieking over our television sets.

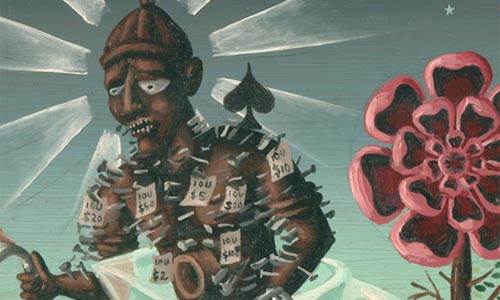

Ostensibly, Matt Couper’s work is a play on traditional Spanish colonial devotional art. From the thin tin surfaced ex-votos to the deep reds and blacks of the canvases, without exception all of his works carry the grave sensation of the Jesus story: the heavy burden of the cross, the dark desperation of Gethsemane, and the conscious journey into betrayal and ambush. But it would be a mistake to see this as a revival or a resurrection; it’s more of a haunting. Matt is not a Lazarus or Jesus, and if he were a biblical character he’d be an adjustment of John the Baptist, he is ‘voice[es] crying out in the wilderness’. The symbolic density of his work, its thickness, weaves indictments and lamentations with moments of healing and understanding. His dreams are whirlwinds populated by Alf, Starbucks, dollar bills and The Simpsons, all with the bloody gravity of the cross and the great mourning that it entails– the loss of a God and the coma of hope and faith.

+++

It should come as no surprise that Matt has moved his base of operations to the center of this wilderness, Las Vegas, Nevada–the savage jungle heart of the American Dream. Let me be perfectly clear here, if we could imagine a place that embodies the myriad symbols crowding our daily lives: this onslaught of superficial suggestions (in the hypnotic sense), these placeless, timeless, styles of a memory that bombard us in a constant media blitzkrieg, Las Vegas is that place. Matt draws his strength here, in the belly of the beast; it’s his nurturing she-wolf as much as his dreaded nemesis.

The struggle in his art, those screaming, whimpering, and wrestling voices that we all try to forget, those are the deep layers of traumatic historical memory fighting to break free of the flattening, even 2-dimensionalizing curse placed upon them by our spectacle society. These voices are the real aristocratic intrigues latent in Excalibur, the traumatic voyeurism of the actual Circus Circus, the slaves of New York New York, and the Guillotines of Paris. These are the lost morals-of-the-story. Here is the torrent of cognitive dissonance you feel when you look at Matt’s work: it’s not ironic, and we are losing the ability to process that.

To close, I think Matt’s repeated use of the Congolese Nkisi figure provides us with an illustrative example. Nkisi roughly translates into “divine hunter”. The figure, once fashioned in the proper way, becomes imbued with the spirits of the dead ancestors. It acts as the medium between the world of men and the great beyond. This great beyond is, for us, history itself, the great accumulations of souls, spirits and voices, all holding the one attribute that defines divinity as such, the ability to speak the complete truth. The figure becomes an arbiter in the present. Anytime an oath or treaty is sealed, a case tried, or a transgression punished, the Nkisi is nailed as a physical testament. The power of the Nkisi is the power of the social itself, the power of the final word, but also the proof of history and the records to show it.

+++

In Matts work, we can easily say that he is the Nkisi, he is the one nailed, he, as artist, is medium between these worlds. I don’t think this is incorrect. However, I think that the fuller truth is we are all now Nkishi. With the death of God we have lost the final word on truth. There is no way back, not that it’d be desirable to return. Instead, now, like Matt, like the Nkisi, we must bear the burden of truth like nails into our bodies, navigating this confusing world’s litigating demands, desires and uncertainty, all the while displaying the seriousness befitting one with great responsibilities. In the end, I argue, Matt presents us with a profoundly ethical question, how should we bring depth to this superficial world? Or in other words, how can we sanctify the truths of our history in a world of theme parks and casinos? How do we keep that 3rd dimension?

Anthony Morreale 2014