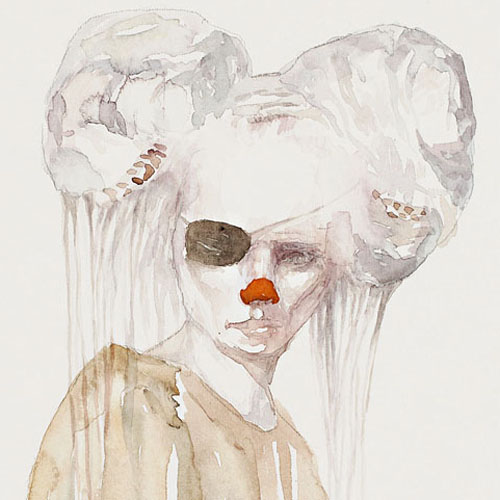

She Draws Like An Angel While She Renders Hell: Lorene Taurerewa's Company of Fools. An essay by Ashley Crawford

There is something definitely wrong about these images.

They are still moments from an alternate reality that we all cringe from. They are the images we see from peripheral vision, from horribly shady reminisces of somnambulistic curses imposed from the unconscious. They are things we don’t want to remember. And yet, why are they so both seductive and familiar, so strangely impelling, so innately parts of our own psyche?

In one image a little girl plays on a swing while her adult doppelganger stands before her. Both are beautiful and yet neither are happy – one aspires to be an adult, the other a child, one dreaming of the other – please allow the innocence, please allow the knowledge.

Then there is the carnival in its most malicious cycle, the horrendous reality of entertainment, the donkey (disturbed), the fat man (suicidal), the black man (the victim), the dwarves (humiliated), the clown wards off demons but is defeated, the pederast looms behind, awaiting a feast of brains. The Wiseman, or at least the skeletal remains of him, walks off stage in disgust. Elsewhere the dominatrix oversees her minions, her simian whip amply readied to apply, her subservient, be-suited suitors gaunt and wounded, supplicants one and all.

Lorene Taurerewa is a storyteller, pure and simple. Her viscous and vicious narratives fall somewhere into the ether world populated by the likes of Hans Christian Andersen at his most extreme (the mangled feet of a child in The Red Shoes), Joel Peter Witkin at his most baroque excesses and David Lynch with his macabre mis en scenes. Taurerewa’s short stories are compiled in a sensuous and sinuous narrative line. Her twins are the brothers of Kubrick’s sisters in The Shining via a gruesome Dr. Mengele fantasy. Her clowns are a bizarre melding of Hans Bellmer and John Wayne Gacy. But despite – or perhaps because of – their ultimately macabre stories we are drawn into these pictures, seduced by Taurerewa as succubus.

This is in large part due to her sheer virtuoso skill with her media; she draws like an angel while she renders hell. There’s something unnervingly innocent about her horror stories and we, like wee children listening to a fairy story at night, are drawn into her world and we will never be able to quite leave it behind. You can’t quite eradicate these images … they burn into the retina and they return, often at night, uncalled for… unbidden, but always there… waiting.

Ashley Crawford, 2010