The Ties That Bind: Warwick McLeod's Sons of Leod. An essay by Damian Skinner

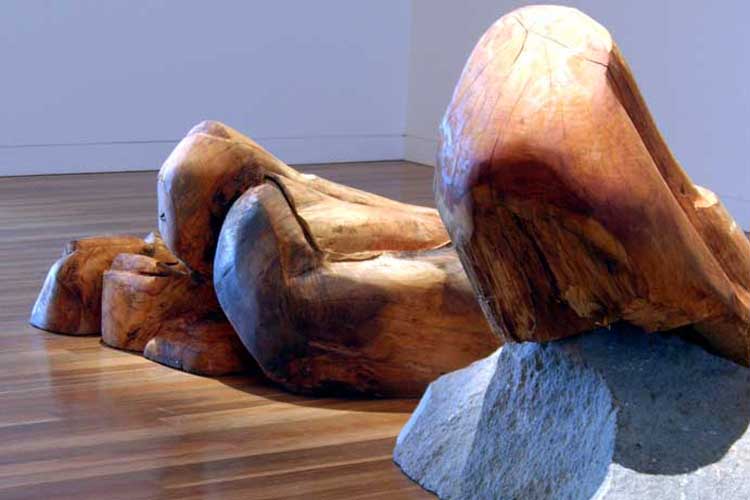

A series of rough-hewn toes and rocks emerge from the gallery floor, and high above them seaweed digits and heads are suspended on long, thin poles. The toes, which are carved from the timber in a way that respects the wood’s natural form, cling to the rocks like seaweed, morphing from the floor of the gallery. The seaweed, bound and woven, reveals itself as hands and heads, impossibly monstrous, like the bandaged appendages of a mummy. The seaweed is hand and kelp at the same time, the image formed without disruption to the natural quality of the material. The wood, similarly, is foot and timber. These objects anthropomorphise in a way that is uncannily like the tricks we perform on nature – seaweed as flowing hair, or tendrilling fingers, body parts of some unknown force of the deep. Or the tree stumps, giant and inert figures threatening to assume life and movement. This part of the installation is deeply creepy – just not, I want to say, although I am aware of the irony, natural.

Sons of Leod is, according to McLeod, ‘about the creation of identity out of will.’ Drawing on the museum’s power to recreate a (fictional) totality out of parts, the installation brings together heads, hands and feet to suggest ancient beings that are long forgotten. A kind of ‘display in a natural history museum of a paleontological find,’ the installation is created from ‘strange formations…in the form of feet clinging to the rocks of an ancient shoreline...these were discovered in the breaking of ground for the museum's foundations, and it was decided to preserve them, to build the museum around them’; and ‘seaweed heads and hands’ recently washed ashore on a nearby beach. In an act of scientific faith, ‘They have been brought into the museum and an answer to a strange mystery has been pieced together and postulated – namely that these finds from distant ages are indeed the hands, heads and feet of five people. The museum has positioned these with booms and cables, as it would to reassemble the incomplete skeleton of a dinosaur, to reconstruct the identitites of these people.’ According to McLeod, the will to reconstruct on the museum’s part is matched by a longing for communication found in the gestures or sign language of the body parts: 'each person entreats with an open hand, asking for information or contact, while the other hand is held in a gesture of purpose – of knowledge, instruction, prophesy, warning, or blessing’.

He said the dead had souls, but when I asked him

How that could be – I thought the dead were souls,

He broke my trance. Don’t that make you suspicious

That there’s something the dead are keeping back?

Yes, there’s something the dead are keeping back.

The body of the ancestor is a complicated figure in this exhibition, the source of numerous anxieties and tensions. While McLeod frames the spirit of the show in a tone of neutral exploration, Sons of Leod reveals most explicitly the sense of horror that can come with confronting the past. There is something monstrous about the heads, hands, and feet in this part of the installation. The aesthetic is definitely grounded in the representational operations of the horror genre. The woven body parts suggest the unassimilable difference of a figure like The Wicker Man, the core motif from Robin Hardy’s 1973 movie, in which a naïve policeman from the mainland becomes a sacrifice for a pagan fertility cult, burnt alive in a wooden effigy. If, as McLeod indicates, the hands of these half-completed figures indicate the desire for communication, the prospect is not a very pleasant one for the living. When the literal bodies of the past resurface in the present, the effect can only be terror. Witness the climactic scenes of poltergeist, Tobe Hooper’s 1982 movie, in which the human remains of those not removed from the burial ground begin to rise from their disturbed sleep. The puzzle of the supernatural is explained, but these bodies represent an unsolvable problem, because the dead and the living can’t easily share the same geographical location.

Damian Skinner 2005