Spirit and Form: the art of Lorene Taurerewa. An essay by Owen Davidson

At a time when Painting is suffering a serious dip in prestige, perhaps it is worth noting the issues that are basic to the medium. These issues are also the reasons why painting is the most conceptual – as distinct from the smugly conceptualist to which we have become inured – of all mediums, the natural medium of ontology.

Among painters, painting is known as “the great struggle”: it is the struggle to make dimension, to pull a space out of the flat canvas into existence in the present world, by power of the imagination and the skills of illusion; it is the struggle to contain time - the actual time it was made, the time of intense focusing, compressing of thought, feeling and memories into that precise time when the paint is going down, in the act of painting; and it is the struggle to actually reach and make contact with the idea, the vision or the memory, to which painting can only ever allude. At the bottom of every painting lies the dilemma of futility. Painting is a futile effort to bring about an existence, an effort doomed to failure by the facts of painting: 2-dimensionality, allusion, illusion, timelessness.

This struggle the painter never wins; the canvas – flat, relentlessly indifferent, always wins. But when the fight is in real earnest, the painter’s concentration is really finely focused, and it sears itself into every mark put down. Traced there we see a struggle parallel to the struggle all of us face in every aspect of our own lives – the struggle to be somebody, created from our own will, and not just the passive creation of circumstances. This is how a painting communicates with us and talks to us about our lives and our selves.

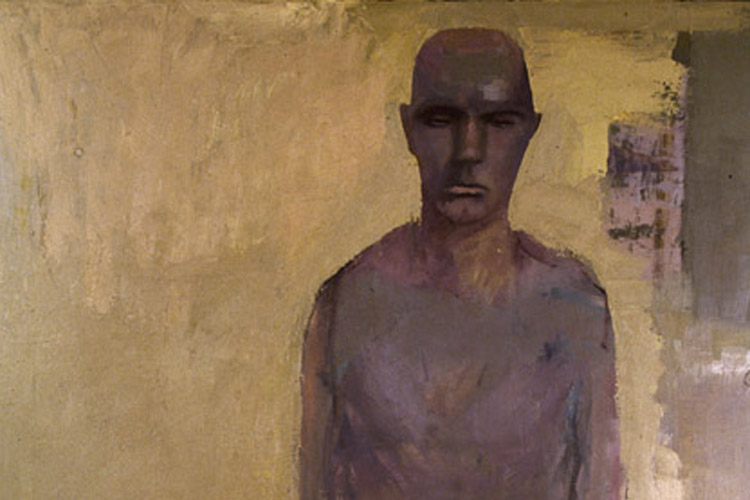

Lorene Taurerewa's canvases are the height of an average person. In each painting, a single figure tries to find room in which to be; forming itself from the flat paint that surrounds it. There is an immediate confrontation between viewer and painting - that is to say between the viewer and the rectangle itself, not just the figure in the painting. The painting presents itself as an alternative psychological world, bounded by the same dimensions as the psychological world that is inside the viewer: if the viewer could unroll himself, herself, like a canvas, that canvas would be the same dimensions as this. And the viewer might feel much the same as this figure, feeling the tyranny of 2-dimension-ness, of being trapped in the world of imprint, of record, of allusion.

Anyone who has ever felt the claustrophobia of striving to become one's own self within the confines of an identity prescribed by society, by family, by genetic inheritance; any such person will have a long conversation with these paintings. And in this conversation, what will you hear? You might come away in hopelessness, from hearing confirmed the knowledge there is no way the other figure could ever break through to our side of the canvas. Or you might come away strengthened, empowered from hearing the muffled voice of a kindred spirit trying to get through from the other side to help us.

Why a kindred spirit? This unavoidable feeling comes directly from observing, in the paint, the struggle of painting. The plane of the canvas situates two forces on either side of it; they haul towards each other in a kind of tug-of-war in which these two identities strive to near each other, and join in the canvas itself. There's the force of the painter’s will, working in present time in front of the canvas: and then there's another force, that of an identity that urges to be brought into being out of the distant past; this identity is within the painter, but it is not owned. It is as unconscious as unrecollected memory or genetic conditioning.

The kindred spirit is always an androgynous figure; neither woman nor man but just “being”. It’s very specific in appearance: naked, always bald-headed, broad-shouldered, wide in the hips, genital-less. For all its specificity you know there is no life-model sitting for these paintings. These aren’t portraits or even self-portraits; not in the sense of having been made from observation. But they are self-portraits in one deep sense.

Anyone who has taught life drawing for any time knows that before a student has become taken up in the techniques of observation, the drawings they make will often have an uncanny resemblance to themselves, rather than to the model: this is because the information that comes to the hand from the eye is being drowned out by the information that comes from every other part of the drawer’s own body –the length of the limbs, the weight in the legs, the tension in the face; this is all information that influences the judgments the drawer makes, unconsciously. When a drawer or painter has no model to observe, all information will come from one’s own body; and not as outside information to be interpreted or translated by choice, but as immeasurable, non-negotiable, physical fact. When the figures are life-size like this the transference between the painter and the figure on the canvas is as close as a body-print: but not a print from the surface of the body, a transference from within the body.

What ends up being painted is a genetic command, heard within the painter’s body. This is an ancient command, which will be brought into being, just as it has been for generation upon generation. This kindred spirit is kindred back through the generations, and you cannot think that there was a time when it was not. It is the ancestor, seemingly.

It sits there solid as a rock and just as still; peers out of the canvas in silent questioning, as concentrated and inscrutable as a monk. It perches on a shelf incised into the middle-ground, and stares at us across the impenetrable distance between; like a prisoner brought up from the cells trying to negotiate through sound-proof glass. Through the gravity of its thought it sinks towards us. Its shape is pushed and squeezed by the surrounding space, while the space behind and in front of it remains impenetrable. It seems stuck in the middle-distance for all time.

Most often the arms are folded, motionless, restless, in the lap. Other times the back of the hand is presented to the viewer, as if to hide what the hand contains. But the fingers are opened - the hand cannot be grasping anything but empty space. Maybe, in an automatic gesture, the kindred spirit is imagining holding what it wishes to possess - real space, just like ours, in which to be. But with the same action it pushes the back of its hand against the glass to demonstrate the impossibility of contact and, implicitly, push us away. The gesture also implies question, uncertainty, hesitancy; as if the kindred spirit is trying to define, by means of sign language, what the meaning of the conversation is. Do you mean me? Or, the beginning of a language in signs where no definitions are sure, I? Am I… to you? Are you…?

To make the contingencies of painting - the vision of form and space, the facts of non-form and non-space – to make them narrate like this takes considerable skill with the brush and the paint, considerable knowledge of drawing and colour. Ms. Taurerewa shows an understanding of colour - a knowledge of the spatial principles of chroma, hue and value - that is rare to find in New Zealand art. And the drawing is particularly strong. At times in these paintings, the initial lines that construct the figure are left, so that the painting looks like it is caught somewhere at becoming a painting out of a drawing.

Which invites a look at the drawings themselves: these are of a similar scale to the paintings. Life-size, they are equally confrontational. Just as with the paintings, the striking thing about the drawings is an immediacy and power of the concentration that is focused in the act of drawing. There is a great deal of raw talent; there is also a great deal of skill and evident training in the knowledge of mark, the knowledge of volume and especially the knowledge of composition. The placement of the mark and the direction of the mark directs itself as much from the shape of the surface on which it is going down as to the form of the volumes it is trying to create. Just as with the paintings, you have a vigorous struggle going on, continually making the drawing - the 3-dimensional form is really trying to bust out of the confines of the paper because every mark grapples with the facts of the paper as much as it pushes the hopes of the form.

Often there will be a couple of figures, one more fully rendered. Their bodies are more restless. Hands gesture, as in the paintings, but in the drawings they accuse indifference, or demand communication. As in the paintings, forward space and backward space are uninhabitable. If a limb stretches forward, it leaves form and becomes line. A figure in backward space struggles to push itself out of the paper - a figure moving forward out of the paper becomes line, leaving an after-image of the place it held. This leaves only the middle distance as a place to be, stuck and immobile, trying to communicate with sign-language.

Their impassive faces seem full of caged immanence, full of thought in the back of the mind, which their stone-like permanence keeps stopped from action. About what they are thinking, is nowhere literalised: however the two people often look similar, as if they are the same person at different times or different places in life - or perhaps they are blood relatives. It is certain that one fully sees and occupies the mind of the other. They are kindred spirits.

You can see some of what is suggested in these paintings and drawings confirmed more literally in what is evidently an earlier piece - because quite a bit less sophisticated in its colour. This is a triptych, in which birds flutter out of the frames of each of the two paintings. The figures in either painting hold their hands in a position to suggest they have just been holding the bird, which has escaped. And yet so careful is the gesture that we know it has been guarding the bird's fragility - perhaps the hands' clasp was not imprisonment but protection. The fingers are painted with delicate brushstrokes which lend the hands the same qualities as the feathers, and evoke the sensation of the fluttering of wings against palms. The gesture of the hands is also one of prayer, as if the figure, though having lost something very cherished, blesses the bird and prays for its flight.

With its taught, fanning fingers and bared pate, the figure pushing itself out from the wall, between the two paintings, resembles both the escaping bird and the person in either painting; inviting the conclusion that all beings in this triptych are the same being.

In fact nothing in the whole piece is or can be. The triptych is about a state of being that has been missed or is just to come. The sculpture is a body-cast; that is not a form, for the form (the model) is absent; but a time - the precise but unlocatable leaf of time when the alginate set, preserving the flutter of expression over the model's cheeks and eyelids. The figures in the paintings cannot enter 3-dimensional form and be; the 3-dimensional figure in plaster cannot enter time and be.

This kind of juxtaposing of painting and sculpture is just how the altarpiece triptych works in medieval art. Journeying through 3-dimensional space, walking up the nave of a cathedral, your path ends at the focus of the whole space, the altar; and on it, closing off the space like a folding screen, the altarpiece triptych. At this point, only the spirit can journey further. Painting guards the spiritual world from the physical world, and ensures the only way to enter is to leave one’s being as a person shaped by the realities of the world, and become a person of faith, ready for death. Here, in the receiving of the eucharist and the contemplation of the altarpiece, the sacred mysteries of the incarnation of the spirit are felt and contemplated.

The medievals knew about Painting’s special relationship with the imagination, with faith, with passion, and with the unknown power that resounds within us; and that it is only through these that we come into contact with the Spirit. In this age, of the effortless congratulation of the literal, people will more often turn away from the sight of power. But people do still need the spiritual; and a large debt of gratitude is owed to those who still try to find the paths.

Owen Davidson 2005