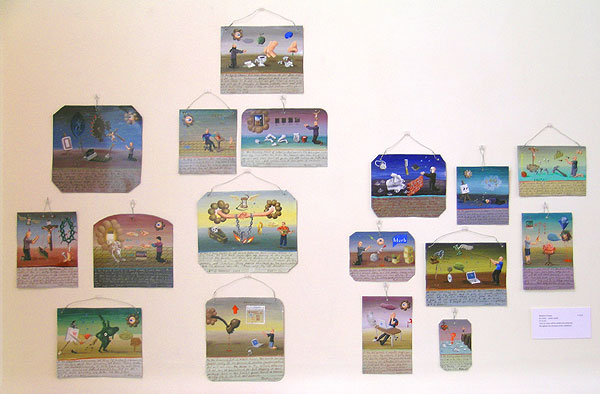

Matthew Couper's Ex Votos. An essay by Gerald Barnett

Since leaving art school in 1999, Matthew Couper has produced a body of work notable for its formal variety, skilled making and provocativeness. From the outset, his work was an uneasy mix of unfashionable oil painting ("so last-century" to quote Couper) and a precocious cynicism about the machinations of the art world, with its private and institutional patronage, taste-makers and insider-ism.

For a while it seemed his preoccupation with the local art world was not going to be enough to sustain his artistic ambition. But travel to Europe and the United States gave Couper a wider and deeper conception of art. He ‘discovered’ at first-hand the Western painting tradition – Italian pre-Renaissance and Renaissance painting in particular. Fra Angelico’s famous frescoes in the monastic cells of San Marco, Florence, made a deep impression. They are among the supreme works of the Renaissance. Even in our secular age, it’s difficult for an artist not to be affected by the fusion of religiosity and artistic expression.

More recently, Couper was attracted by the Mexican folk tradition of ex voto painting: small paintings – usually on tin or wood – that depict scenes of saintly intercession in ordinary lives. The image is accompanied by a hand-painted text, usually addressed to a saint giving thanks for intercession, or praying for it in the future. Like the vigorous Latin American form of Catholicism that gives us the saints, ex voto painting has proven a persistent if humble art form. Two hundred years ago, a Mexican farmer might have commissioned the village artist and sign-maker to paint an ex voto giving thanks for the ‘miraculous’ cure of his wife’s fever. Or a merchant might pray for his own safe passage through bandit-infested mountains he must cross to trade. Today, in urban Mexico, ex voto paintings give thanks for a lottery win, deliverance from a slum landlord, or protection from violent crime.

Couper’s ex votos are brimming with his art world obsessions, his travails as an artist as well as his enthusiasms. His musings are in a ‘voice’ somewhere between Robert Crumb’s comic book confessional and the so-called ‘abjection’ of Sean Landers’s text paintings. His address to various fictional saints is a disarming mix of diaristic plain speaking and irony. The small format allows almost spontaneous capture of passing images and states of mind – the frustrations and privations as well as the exhilarations – often born of the daily grind in the studio where he works on big, complex paintings. Thus, there are ex votos addressed to: "The Crucified Christ Of Turning Tides And Art Awards…; …The Dirty All-Seeing Eye Of The Art World Mafia…; …The Ghost Of Andy Warhol And The Attitude Of Lou Reed…".

The collected ex votos are a fluently painted, candid narrative of the young artist’s struggle. "Financially, being an artist sucks". He contemplates getting another job…"Haha, Not!" His car is pranged, causing another financial crisis and a ‘prayer’ to the "Christ of car repairs". That’s him on the crucifix with carburetor and spark plug completing the ‘trinity’. It’s salutary to see how often money is the problem. No artist wants to starve in an attic for his art. Perhaps the miraculous thing here is that, despite the artist’s troubles, his art exudes ambition and humour.

Gerald Barnett