Death And Resurrection In Las Vegas: A review of Matthew Couper's exhibit Horror Vacui. An essay by Jenessa Kenway

The gallery was permeated by the staccato of small cards slapping back and forth on wrists. Attendants wearing ball caps aggressively flapped the cards before offering one to each guest during the opening of Mathew Couper’s exhibit Horror Vacui. Instead of a stripper’s starred nipples, the card depicted a painting from the exhibit, needlessly censored in places. Mimicking the porn card-pushers who nightly line the Strip is just one way Couper appropriates and comments on the Las Vegas experience.

The gallery lights have been noticeably dimmed and large paintings on wooden hinges swing out from the wall, casting shadows; the effect is subterranean. A video diptych runs clips from the film Nosferatu, showing the vampire rising from his coffin along with footage of casino implosions running in reverse.

The catacomb-like environment, the vampire casino montage and paintings of casino logos (Flamingo, Tropicana, Dunes) popping out of coffins all drive home a metaphor of Las Vegas as both resurrection and undead experience. Casinos are destroyed and new ones rise from their graves. Throngs of tourists lurch in zombie-thick packs, intermittently offered meals, tickets, topless dancing and other pleasures of the flesh by the ubiquitous card-flickers.

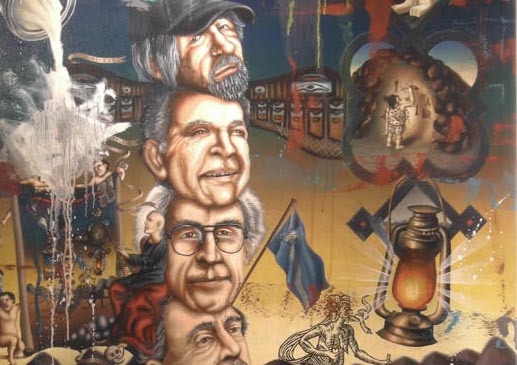

Scattered throughout the exhibit are graphite cameos of persons who figure prominently in the historical milieu of Las Vegas, such as Howard Hughes, plane-crashed starlet Carole Lombard, burlesque dancer Holly Madison and Steve Wynn. Las Vegas contributed to the immortality of each.

The cycle of death and rebirth feeds into historical and political themes in a painting of a snake symbol found in an old political cartoon by Benjamin Franklin. The original drawing demands “Join, or Die,” each severed serpent segment labeled with the initials of a state. Couper replaces state names with popular fast food joints — Wendy’s, McDonald’s, Panda Express — making the new mandate to “join” obese consumerism or “die,” the surrender to which is slowly killing thousands.

Couper’s work even goes so far as to suggest art itself is facing resurrection. In the center of the space, a replica of the white-and-red-cubed grave marker of artist Kasimir Malevich rests before a fresh grave, shovel still resting in the soil. Malevich is known for his disturbing piece, “Black Square,” signaling the death and the rebirth of art. Within the black void Malevich intended to paint “the face of the new art.” In lieu of a zombie arm popping out of the grave, Couper gives us a rough sketch of the controversial Warhol portrait discovered at a garage sale in Las Vegas. The image invokes a work hovering between rebirth and acceptance back into the world, or languishing in the purgatory of questionable legitimacy.

The exhibit’s title references the physics concept that nature does not tolerate vacuums, as well as the art concept expressing fear of empty spaces. By packaging the two, Couper simultaneously rejects voids and demands the filling of space. Vacancies created by the passage of one object must inevitably be filled by something or someone else. And, of course. Las Vegas is all about filling vacancies. Hotel rooms empty out, slot machine seats are abandoned and snake eyes come up at the craps table — all soon refilled with a fresh batch of visitors.

Locating Las Vegas within a cycle of death and rebirth is a darkly fascinating and grim prognosis for the city. As we are consumed by the entropy of the current cycle, a question surfaces: What will the next phase of rebirth hold? To paraphrase Malevich: What might the face of the new Las Vegas look like?

Jenessa Kenway 2014