The Divine Self and the Church of Auto-Resurrection. An essay by Peter Howland

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you...

‘Song of Myself’ by Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

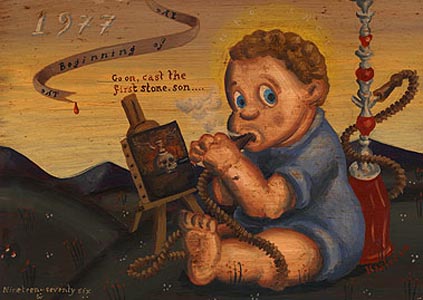

When I first meet the quietly spoken and inquisitive soul that is Matt Couper to discuss writing this article he said that 33, 27 and rites of renewal where important notions that underpinned his (glorious) Thirty-Three retablo (and yes, I am an unabashed fan!). The numbers 27 and 33 refer to the ages of notable – or at least famous – individuals who have died young and the pseudo-cults that have arisen after their wakes. The 27 Club (aka Forever 27 Club or Club 27) is a cabal of demigod musicians – most notably Brian Jones (founder of the Rolling Stones, 1942-1969), Jimi Hendrix (1943-1970), Janis Joplin (1943-1970), Jim Morrison (1994–1971), Kurt Cobain (1980–1994) and most recently Amy Winehouse (1984-2011) – who died in often-framed ‘mysterious circumstances’ at the self-indulgent age of twenty-seven. Although exactly what is mysterious about drug overdoses, asphyxiating on vomit induced by ingesting copious amounts of sleeping pills and wine, and suicide by shotgun, quite frankly escapes me – as does the fact that the cohort of musicians who died at ages other than 27 is considerably larger and yet receives virtually no cultic attention. Nevertheless the adulation that the 27 Club attracts is clearly driven by the call to live fast, die young and the music plays eternal, which since the dawn of rock ‘n’ roll in the late 1940s has been the sacrosanct shout to arms for all those who intuitively rebel against the sobering effects of a 9-to-5 existence.

Club 33 (if one exists) really has only one member - known by some as the member – Jesus Christ, who many believed died (at least in earthly form) when he was 33 years old, although his exact age of crucifixion, death and resurrection could have been as late as 35 years depending on the faith (biblical, historical, astronomical) one deploys for such calculations. Christians believe that Jesus Christ was, is, and will forever be the Son of God sent to wipe clean the slate of Adam’s original sin. In contemporary parlance, the intentful sacrifice of Jesus Christ rebooted humanity’s hook-up with God, thereby enabling the righteous to achieve eternal salvation, the wicked everlasting damnation, and the merely bemused the immanent purgatory of Survivor Island, America’s Next Top Model and other equally asinine TV shows.

The earthly aspirations and ideals of the members of 27 Club and Club 33 are renewed through various symbolic and ritual performances – by spinning vinyl or uploading iPods, drinking Jim Beam and wearing Jimi Hendrix t-shirts, intoning the Lord’s Prayer, attending Sunday mass, and/or by confessing one’s sins and receiving Holy Communion. Rituals of renewal are a stock and trade of anthropological enquiry. Typically they involve some form of ritualised sacrifice or gifting that enables individuals to enter the realm of the sacred, commune with their ancestors, deities or gods, and express their gratitude for any divine bounty. This ritualised gifting characteristically takes the form of food or animals left on an ‘altar’ and sacrificially devoured - burnt or bleed, although just as frequently the actualities of sacred consumption are performed by the ritual participants themselves, which is surely a great justification for enjoying a hearty feast and the fellowship of like-minded souls! For example, the mid-autumn Chinese Moon Festival and American Thanksgiving held in November are annual celebrations in which the ‘fruits’ from the season’s harvest, such as moon-cakes and pomelo in the Moon Festival and pumpkin pies and roasted turkeys in Thanksgiving, are symbolically gifted to Chang’e, goddess of the moon and to God respectively.

Repeated cycles of ritual sacrifice/ gifting thus perpetually renews the enduring and reciprocal relationships between humankind and the sacred, and thereby ensures that divinely provisioned bounty is continually replenished. Even though contemporary Thanksgiving celebrations are now situated in a thoroughly industrialised world that is doggedly distanced from the spirituality of nature, the ethos of communion with, and gratitude for, the divine is nevertheless still evident. Indeed many rituals are a mixture of historical echoes and current day concerns, and Thanksgiving celebrations have evolved into a hegemonic rite of patriotic fervour that gives thanks for Americans as God’s own emissaries on earth and legitimates their divine right to be the global champions of life, liberty and the World Series way.

One of the most famous cycles of ritual renewal and human/divine gifting within anthropology is the Maori practice of hau, which refers to the ‘spirit’ of the forest that provisions food and more generally to the spirit of all gifts. Bought to anthropological fame by the French ethnologist Marcel Mauss in his seminal work The Gift published in 1950, hau manifests in Maori lore so that hunters returning from the forest laden with birds are obliged to give some to their local priests, who then cook the birds in a sacred fire. The priests eat a portion and then prepare a mauri – a talisman that is the physical embodiment of the forest hau, which is then gifted back to the deities of the forest in ceremony called whangai hau (translates as nourishing the hau). This ritualised gift exchange appropriately acknowledges the mana (power, status) of the forest deities, gives thanks for their beneficence, and ensures that the forest remains abundant with birdlife. Moreover, hau ideally imbues every gift exchanged within Maoridom so that when one party gives an article (taonga) to another, who in turn exchanges it to a third party, any increase made in the last exchange must be gifted back to the first party – thus taonga is inalienably associated with the original giver, individual profiteering is summarily inhibited, and exchange relationships are maintained at the level of reciprocal gifting. As the philosopher Lewis Hyde notes: “Capital earns profit and the sale of a commodity turns a profit, but gifts that remain gifts do not earn profit, they give increase…in gift exchange it, the increase, stays in motion and follows the object, while in commodity exchange it stays behind as profit” (2006: 38)

In Matt’s arresting body of work Thirty-Three a bricolage – of rituals, death, renewal, gifts, commodities, creative increase, worldly profit, the profane, the divine, science, philosophy – especially ancient Greek and Maori – and artistic influences and history rousingly evidence a contemporary creative presence that is openly idiosyncratic and yet instantly recognisable, persistently questioning and aspirational, and at times, skeptical and frustrated. At first blush Matt’s paintings can appear profoundly individualistic and an exercise in the sort of retrospective justification that many of us spin whenever attempting to explain our own life’s journey. A popular (and I suspect typically anthropological) response to Thirty-Three would be that the type of narcissistic excess routinely generated within the dog-eat-dog, hedonistic, and shamelessly conceited existence of market-enamoured, post-industrial societies such as New Zealand, Australia, USA, and elsewhere – which is either a brutality or an enlightenment, depending on where your moralities lie. A more sober and analytical response would be, however, that Thirty-Three effusively reflects and reproduces the ethos of institutional reflexive individualism that has increasingly dominated life in the first world since the mid 20th century.

Institutional reflexive individualism emerges within what sociologist Ulrich Beck calls the ‘second modern’ or ‘second modernity’ – which is characterised by the insistent rejection of the ‘first modern’ (i.e. 18th-19th century) ideal of a rational, universal, and unified world. Reflexive individualism is essentially a form of self-orientated, self-referential, self-assembled and self-motivated personhood that is typically pursued via personal lifestyle choices, autobiographical narrative, and voluntary identity associations – essentially the ‘I am whatever I chose to be’ syndrome. This ethos contrasts with the socio-centric personhood characteristically found in kinship or ancestor-based societies in which individuals are most likely to define themselves by their social connectedness to others – as the ‘son’, ‘sister-in-law’, ‘trading partner’, ‘enemy’ of – and then act in accordance with the sociality expected of such relationships in any given context. Some scholars argue that reflexive individualism is a freedom that emerges with the evolution of meritocratic (aka democratic-capitalist) society and which emancipates the individual from the tyranny of kinship obligations, rigid religious knowledge, heredity politics and other similarly fixed ‘traditions’. Many of my anthropological colleagues rightly object to such a reflexive modernization thesis. They note firstly that reflexivity is a universal process of socio-cognition and one through which all humankind generates a sense of self that manifests as I and me compared to we and them. Many also object that the thesis rest untenably upon the construction of a ‘traditional’, kinship-based, and non-reflexive Other; and equally upon the Euro-evolution of a pure reflexivity that is relentlessly fuelled by radical questioning and doubt, an undertaking that is only really sustainable in theory or ideology, and which is quickly marooned on the routine pragmatics of everyday existence.

Yet what these naysayers tend to overlook are the consequences of an economy of limitless expansion, accumulation and technical innovation that emerged with the industrial revolution in Europe from the 1800s onwards. Firstly, money has become evermore pervasive as a medium of production, exchange and consumption; in addition, capital is increasingly mobile so that now approximately one trillion US dollars traverses the globe everyday in search of more profitable investment. This inexorable shift toward uber-capitalism has compelled labour to be similarly fluid or flexible in terms of geographical sites of production, constantly changing skill-bases, and short-term employment contracts. Furthermore, commodity-markets have not only exponentially expanded (in terms of new products and markets), but the social distinctions and statuses once associated with consumption have become increasingly fuzzy or indeterminate to the point that few of us are now truly shocked by a plumber who is an opera buff or by a solicitor who is a petrol-head. Just as significantly, phenomena such as knowledge – scientific, religious, common sense – now characteristically takes the form of hypothesis and is continually open to critical revision, while authority is likewise perceived as multiple, divergent and contestable. Doctor, iridologist, guru, your next door neighbour, or simply an interested bystander, consult them all whenever that mole on your forearm begins to itch – all will have something to recommend as you commence your battle with, and ideally defeat, skin cancer. Just as significantly, sociality is now elective and routinely based on personal predilections, sentiments, and preferred birth control methods – thus we continually choose, accept and cull, with Facebookesque panache and anxiety, our sequence of lovers, friends, and familial connections (including planned pregnancies and choosing to forget Uncle Tom’s birthday). Besides this our post-industrial existence is marked by the persistent compartmentalisation of life’s institutions and we are habitually subjected to disparate, even contradictory, demands upon our selfhood, personhood and social status. A king in the supermarket, serf at work, an equal in the bus queue, a dud or stud at home – and add to the mix that any of these personas may be either actual and/or illusory at any moment in time.

Within the flux of the second-modern there appears to be a persistent expansion, oscillation and atrophying of alternative subject positions, socialities, and life-trajectories (or life journeys as they are euphemistically known) – all of which structurally compels, and ideologically induces a strong desire for, reflexive or self-referential individuality. As Beck notes, within the second-modern ‘the human being becomes … a choice among possibilities, homo optionis’ (2002: 5). Everyday we are structurally obliged, as individuals, to navigate a diversity of institutional regimes – to chase educational qualifications, occupational promotions, to re-skill, re-train and update our CVs, and to independently adopt (or adopt independently) political viewpoints, religious beliefs, or non-religious convictions. Everyday we are equally compelled to personally negotiate and create a multiplicity of personas – employee, Joe and/or Jane public, civilian voter and tax-payer, lover, ex-lover, reinstated lover, reaffirmed ex-lover, friend, acquaintance, enemy, parent (co, step, solo or sole), child, sibling, neighbour, anxious or confident self. Contemporary life thus manifests as an existential treadmill of perpetually reasserting, reaffirming, renewing, replenishing, resurrecting and/or re-inventing ourselves in response to the evolving demands and disciplines of life’s institutions – and for those of us inevitably sliding toward senility, simply remembering who we were yesterday. This may even include rejecting one’s biology if it fails to conform to one’s reflexive aspirations – at least if the television advert promoting SureSlim dietary products is to be believed: ‘Never forget. It’s not you, it’s your metabolism’.

Many social rituals in New Zealand, and especially those that transform and affirm us in social role and status, are those that we personally negotiate - either by ourselves, or in union with voluntarily selected others. For example, getting a driving licence, buying a beer in a pub or having sex for the first time (and the last!), purchasing a house, getting divorced, are all rituals that transform and create us as social beings, but which we essentially tackle as individuals. These rituals are simultaneously social and individual, or more correctly are socially individualistic – thus the 40-year-old Virgin was deemed a failure because the sociality of sex had remained primarily a matter of his own hands. Moreover, some of our most common public rituals are likewise celebrations and social affirmations of the individual – for example, birthdays are endemic social rituals and are occasions where friends and family lavish gifts, praise and good wishes upon the ‘birthday kid’ (and not upon the social forces – namely mum, dad, spouses etc – who are socially responsible for the person’s existence in and through time, although these are varyingly acknowledged at baptisms, 21st birthdays and funerals). Indeed, the restless, constantly evolving and embodied change evident in retrospective birthday appraisals of Matt’s Thirty-Three retablo highlights the mobility (occupational, geographic, aspirational) that is constantly demanded of the reflexive, post-industrial individual. Even New Year’s Eve celebrations, one of our few momentous pubic rituals, are occasions for ritually renewing the reflexive self by way of personally ambitious (often overly so) New Year resolutions.

The alleged ‘freedoms’ of reflexive individualism are not equally available to everyone - the working classes, racially marked individuals, the disabled, and others additionally marginalised within market capitalism are perceived to embody fixed identities (physical, sexual, intellectual etc) that restrict or deny their individuality. Moreover, as the sociologist Scott Lash notes be a ‘reflexivity winner’ (1995: 127) is clearly predicated on economic affluence, social mobility and political emancipation – attributes most commonly found among the middle-classes and above. Indeed within the institutions of the middle-classes – especially educational, occupational, political, recreational and social – personal seekership and creativity, self-awareness, self-regulation, independent thought/ action are regarded as a moral right, and individual (typically short-sighted) ambition, CV enhancement, risk-taking, networking, and reward-taking as ethical duties. Not surprisingly the middle-classes characteristically romanticise the meritocratic structures of market capitalism and routinely justify their own successes as personally, rather than structurally, praiseworthy. By contrast the poor, the illiterate, the Third World needy are frequently cast as the engineers of their own misfortune and rarely feature on the ACT Party’s Christmas card list.

In reality embracing the aspirations of reflexive individualism is a precarious, even illusory enterprise, and many find themselves anxiously trapped in the fissure between what the sociologist Zygmut Baumann calls de jure autonomy, that is the agency assigned by society, and de facto autonomy or the actual freedom to make choices (2000: 16-52). Consequently many are drawn toward areas where they perceive personal autonomy is optimised – educational and occupational pathways, life politics, the elective sociality of friends and lovers, consumption and lifestyle choices, body cosmetics, and various identity projects. Not surprisingly the capacity to enact personal choice, however limited in social consequence, is widely considered a cornerstone of reflexive individualism. Reflexive individualism essentially casts the individual as the architect, builder, realtor and resident of their own destiny and thereby deflects critical attention away from the many structural impediments to success – the primary one being the essential pyramid structure of economic power in market capitalism. For these reasons I favour the argument that institutional reflexive individualism is a structural discipline, a compulsion, a violence – one that may be sugar-coated in the ‘ideals’ of personal liberty, meritocracy and the democratic ‘freedoms’ of choice, but one that primarily ensures that the coffers of our economic and political overlords remain full to overflowing.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Firstly, institutional reflexive individualism does not necessarily result in narcissism, although it is by no means uncommon nowadays to encounter egomaniacal music and movie celebrities, dodgy property speculators on reality TV shows, MTV jackasses and their legions of adoring, infantilised fans – not to mention drivers who changes lanes without indicating, who cross the centre-line on mere whim, and who adroitly manage to parallel park their compact hatchbacks while filling up two car-park spaces. Rather, individuals are institutionally compelled to engage the world around them from the perspective of their ego outward. Thus someone who purposefully donates to worthy causes and then responds to the IRD’s call for charity tax credits is socially cast as a reflexive altruist. Indeed anyone who utters ‘I think…’ ‘I feel…’ ‘I had a wonderful time in Fiji…’ is reflexively responding to the social demands and disciplines of institutionalised individualism. Secondly, although power in general is inescapable, the historian Michel Foucault astutely observed that the seeds of discontent, rebellion and even revolution always germinate within specific institutions of authority and domination. Thus anyone privileged to be the beneficiary of a first-world, liberal education – especially in the arts, humanities and social sciences – is most likely to have been exposed to critical ways of reflection and analysis, which of course includes laying bare the various regimes of power, privilege, domination and subordination that function in any epoch – past, present or utopian. Clearly Matt Couper has been exposed to such influences; indeed my knowledge of contemporary artists with similarly critical dispositions is that formally schooled or not, they are thoroughly committed to the creative process and maintain a relentlessly sceptical bent with autodidactic zeal. Thus Thirty-Three is reflexive and reflective, ego-centric and socially mindful; a retrospective, yet aspirational, narrative that identifies and critically evaluates the influences – constructive, restrictive and destructive – that conspire to make Matt who he has become. From the taxing spectre of the IRD to the evolutionary (progressive?) promise of Darwinian science, the Machiavellian barbs of the art world to the inspirational talents of Alan Davie et al, the soul destroying routines of curriculum education and paid employment through to the divine gift of creative energy, the dehumanising colonisation of alien-Nations to the transcendence of ancient philosophical teachings, the self-confidence derived from artistic mastery refracted through awards and transnational acclaim to the humble-pie baked in the glare of public apathy, economic recession, artist’s block and gnawing self-doubt – these are the days of Matt’s life. With varying degrees of dexterity, confidence and anxiety Matt orientates himself toward and engages various institutional forces to resolutely forge (and renew ad infinitum) an ego, a personality, a selfhood – a reflexive individuality – that he desires, indeed is structurally forced, to live by… and so say all of us!

The retablo or devotional paintings of Thirty-Three, each representing a year of Matt’s life, explicitly reference the birthday gifts he has received – accepted, rejected, wondered about bemusedly – over time. They thus reflect the calculative rituals, demands and debts of life that have been institutionally ‘gifted’ to Matt. Yet as a self-assembled and retrospectively reflexive endeavour, Thirty-Three is also Matt’s gift to himself and of course, his gift to us, the external foundations of his life. Matt essentially frames himself as a devotee and an enthusiast in the older sense – an artist, like the great American poet Walt Whitman quoted above, who is compelled to receive the divine gift of creativity, typically in the form of a beguiling muse, and equally bound to gift back with artistic endeavour. Revealingly Matt portrays himself as himself when depicted as an infant (1997 & 1998) or when bared naked and sitting on the shoulder of St. Christopher, the patron saint of travellers (2003). Otherwise the reflexive Matt is most frequently depicted as an unseen presence, albeit one clearly manifested through the mystical spell of influential ‘others’ who most poignantly take the form of different saintly personas (e.g. St Francis, St. Jerome). This metaphorical rendering of St. Matt not only highlights the multiple, dialogic personas he chooses/ is compelled to perform by the compartmentalisation of post-industrial institutions, but also overtly references what founding sociologist Emile Durkheim termed the ‘cult of humanity’. Durkheim argued that whatever was regarded as a common good would be sacralised in any society. Thus one religion of post-industrial society is the individual (arguably consumerism is another) whose rights are valued as sovereign and universal. The secular church of sacred individualism is evident in institutions such as the commonly ignored Declaration of Universal Human Rights, the democratic hoax of ‘one person, one vote’, that justice is blind (but can easily read a bank balance) and the theology of consumer liberation that reaches its zenith in ‘made your way’ Subway sandwiches. Yet have no doubt that individuality of Matt, of me and of you, is sacred, divinely sanctioned and piously upheld by the economic, political and social institutions of post-industrialism, which only ever demand we faithfully resurrect our reflexive selves in accordance with their ever-evolving sacraments. In other words: Sea elogiado el señor Matt Couper – artist, publisher, taxpayer and citizen.

Bibliography

Bauman, Z. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Beck, U. 2002. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and its Social andes. Political Studies, 17(1): 14-30.

Foucault, M. 1995 [1975]. Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. Trans. By Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books.

Hyde, L. 2007 [1983]. The Gift: How the Creative Spirit Transforms the World. Edinburgh: Cannongate Books.

Lash, S. 1995. ‘Reflexivity and its Doubles: Structure, Aesthetics, Community’, in Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order. Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens and Scott Lash (eds.): 110-171. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Mauss, M. 2004 [1950]. The Gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies (trans. W.D. Halls). London: Routledge. Political Consequences. London: Sage Publications.

Durkheim, E. 1969 [1898]. Individualism and the Intellectuals. Trans. By Steven Luk

Peter Howland 2010