In Memory of Water: paintings by Matthew Couper. A review by Warwick McLeod

As the Chemistry of the pre-modern age, Alchemy studied the structure and transformation of the basic building blocks of matter. From the pre-socratics these were assumed to be the four elements - earth, water, air, and fire - with the quintessence aether making a fifth: all matter was some molecular compound of these elements. Because it was assumed these elemental processes would have to mirror those of the larger ecosystem, stages of coagulation, distillation, putrefaction, fermentation, solution, sublimation, and calcination were depicted in the clothes of the alimentary, circulatory and procreative functions of the human body. As tests of advance in molecular understanding, Alchemy set itself specific goals. Principle among them were: the formation of gold; the location of the Philosopher's Stone (a unitary primal element, a manifestation in matter of intellectual form, a kind of secular eucharist); and the distillation of the elixir, or water, of life.

Until well into the 18th century, experimentation in the field of Chemistry - including Newton's own research - had been conducted within the metaphors of this ancient tradition: built into intricate structure from elements of Greek, Roman, Egyptian and Biblical mythology, with foundations in the earliest times of metallurgy. But when the 19th century harnessed electricity, and therewith the power for the first time to examine the structure of matter at an atomic level, the whole Alchemical tradition was thrown out. Thenceforward it could provide a scrap-heap for Theosophists and Symbolists to pick over for psychological allegory; otherwise, only a cautionary tale of the conspiracies of folly, toil, bubble and trouble the laborious mind will weave when it sets off down a path without the guiding light of modern science.

For two centuries now, study of the Ecosystem, from its sub-atomic constituents on up, has been given to this more enlightened science: which in its successes has proven itself so demonstrably right; often to be congratulated, rarely to be humble. Poor Alchemy - so respectful of cycle, so honorific of wholeness: so wrong. And oh poor Ecosystem.

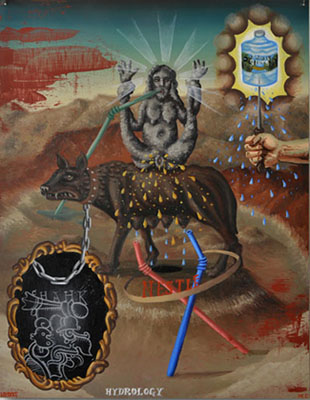

To paint in the imagery of Alchemical Transformative Stages the various processes of our contemporary sciences and industries, as they apply their own strenuous, all-searching, untiring intelligence to a quest to extract the water of life from every possible part of the environment, is to lay an accurate finger on the bitter wound of irony our age is beginning to understand. This show traces, on the backdrop of a declining Lake Mead, the predicament of water shortage the south-western states are facing, and paints its particular local ramifications and quandaries: behind these, studies the making of it in the fatal political decisions of the last century; and surveys behind these still, in constancy with the artist's larger body of work, the ageless reliability of human stupidity.

In setting up the dynamic of the artwork, Matthew Couper's basic technique is simple enough. A genre is selected from art history that is paradoxical to the issue under examination, overlaying them so as to have one provide the backdrop or the costumes for the other. This automatically winds up the clockwork of the painting, for the many mechanisms of irony therein to be variously set into moton, as the eye travels around the picture. In a set of oil-on-paper studies, diagrams tracing vectors of affiliation between multinational corporations are overlaid on paintings replicating images, famous from art history, of the abundance and life-giving bounty of water. Painting them in the colors of Delftware already renders that a subject of nostalgia: so that the tracings on top read like the obsessive greed-plotting of a mind squeezed, in starvation and thirst, to its thinnest, meanest single-mindedness.

Such an accuracy of selection of imagery requires both a precise critical analysis of contemporary politics and culture and an encyclopedic knowledge of art history. A wriggling wrestling-match of irony between tag-teams from art history goes on in every corner of these highly-populated paintings. Here, and in their rational criticality, the paintings are reminiscent of William Hogarth; and in fact they are kindred in spirit with him and with Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray, the English satirists of the 18th century.

It is good to have a breeze from the spirit of the 18th century to refresh our intellectual environment, if it is true that the solutions to America's problems are to be found in the formative ideals of its institutions; as President Obama believed, on faith we now have to urgently question. America can learn a lot from this New Zealander, whose understanding of history, and the historical construction of the individual's perspective, and therefore of the decisions of individuals and social collectives, may be more faceted and cognisant of irony than his American cousins’. Two characters that recur through Matthew Couper's work are twins, dressed in the robes of philosopher-elders, one with a Greek temple for a head, the other with a Maori meeting-house. These represent two modes of thought which broadly speaking could be considered a birthright in New Zealand, where history has left a more even balance as between indigenous and colonial. From their mutual roots in the 18th century, New Zealanders share with Americans the inheritance of and regard for liberal democracy, but from their indigenous history sense that mortal humans actually have no Right to Life; that Liberty is an award of the caprice of history; that one man’s Pursuit of Happiness is likely to be an unhappy experience for those in his path; and that in fact there are no God-given Rights, only privileges, won for you by your forebears, basked in only under the air of entitlement.

America’s history is of the imposition of a new identity - the nation of laws based on Enlightenment principles, its inheritance from Classical Greece and Rome - on a carte-blanche, scrubbed both of America’s previous indigenous culture and of identities shed on the immigrant- and slave-ship; in pursuit of an artificial American dream. Such a wholesale imposition of a willed and manufactured identity can be enabled only by large-scale and remorseless forces operating on its behalf: powerful vectors of population shift and economic change; industrialisation, the acquisition and exploitation of large territories of land, slavery. Dealing with the hypocrisies and willful blindnesses woven into our inheritance from the previous centuries requires an understanding of history as a force larger, not smaller, than oneself as a nation. But America likes to think that the Exceptional Nation makes history, not that history makes it: and this wilfulness causes its beliefs and systems to become steeped in, then calcify within, delusions of manifest destiny. These delusions are headed for a cliff, and we just pushed the pedal to the metal.

Warwick McLeod 2016