The Fable and the Fall: the paintings of Lars Bang. An essay by Lise Jeppesen

The Fable

A fable is a short story that contains a moral. The main characters in the fable are usually animals, but can also be human beings, things or plants. The animals, things or plants have human qualities and can speak and think. They represent different human types, for example the fox is clever and the lion is strong. With Lars Bang there are a number of figures who crop up consistently: first and foremost the children, but also the wolf, the rabbit, the dog, the bear, the snake; and the man, who is often passively observant. Occasionally, interactions between humans and animals occur, and often, as in Grizzly and Gunpowder (2014), it is the children who dress like animals. Through that masking, they assume other animal qualities; are as deadly and dangerous as a grizzly bear.

These figures appear in landscape scenarios that seem almost post-apocalyptic. The symbols are of a civilization in process. Old car wrecks, overturned electric masts, rusty oil barrels and the remains of fences spread out over the earth. Spruce and pine trees are scorched of their needles, toppled trees lie all over the ground, and venerable old trees have been severely cropped with the chainsaw. The buildings are often cheap, foolish constructions. Nearby, you’ll often see a bulldozer, having done its work or lying in wait. One feels the lurking threat of demolition. None of the buildings seem to be suitable for human housing; but often a golden light will shine from their interior, and in a work like Enclave (2015), chimney-smoke rises to the sky to create an illusion of warmth and confidence in the home. In one series of paintings, campervans and caravans testify to the people who populate the scenes as a kind of nomad: as fugitives. In several of the paintings, the yellow sky may reflect a coming sunrise, or perhaps the light from a larger fire. The imagery in most paintings is strangely undefined and fragmented. Some objects have lost substance; while others melt together.

The resolution of the familiar, the recognized and confidential, to embrace a coherent romantic worldview, appears a real situation. But in the backdrop is an unstable, cacophonic uncompromising universe; where it is the individual's ability to change and navigate in relation to the strange, the unknown, which is the determining factor for survival. In one work a man sits in a camping chair looking over the abyss. Lars Bang sees the world as a wheel revolving on a hub. In his works we find ourselves on the outskirts, far from the center.

Lars Bang borrows from the elements, symbols and genres of American culture. The camper is taken from the American trailer park; the man in a cap is almost the incarnation of the American hillbilly; so much so that one can almost hear country music rise from the buildings behind, while he guards his pickup truck. The cowboy hat sends out references to American western heroes, like John Wayne. We get the feeling we are entering one of the many American disaster films, or those TV series about life after the collapse of civilization. Lars Bang's paintings seem to be about a life on the edge; about creating local autonomous enclaves, subcultures where life can be rebuilt.

The Fall

The figures that inhabit the enclave are not immediately endearing. The children are not innocent blue-eyed creatures: but grimacing, troubled individuals; who often wield weapons. They are tough and resilient, relative to the environment's decay. They are enterprising and effective. The boy swings the ax, hunts with his gun and kills a number of animals. This perception of childhood is far from today’s, where children must be protected from tough realities. They relate rather to the children of the original fairy-tale-collections of the Brothers Grimm, before their harsh details and psychological tensions were cleaned up. Here, Hansel and Gretel are left in the middle of the dark forest to die; but manage to discover the man-eating witch and push her into the oven. The children in Lars Bang's paintings have recognized the world's evil and suffered a considerable loss of innocence. But they are struggling inwardly.

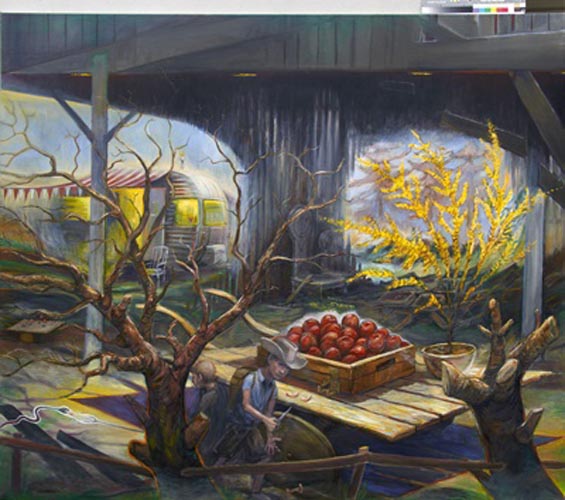

This loss of innocence is apparently debated in Lars Bang's painting The Apple Barn (2015), where a very comprehensive symbolism unfolds. Two boys are in an open barn. Next to them in the foreground of the picture, on an improvised table, sits a large box of red apples. A teddy-bear rests his back against the apple-box. On the table we also find a flowerpot with a golden-flowering tree, within whose branches hovers a dream image of another world: like the window in the caravan of the background, this tree throws light over the landscape. The tree is matched by two other trees in the foreground, one cropped so thoroughly that there are no branches left. The other has lost all its leaves. Apparently they are dead. Perhaps the apples are picked from the golden tree, or they are the last existing apples from the other trees. In any case, the boys are ready to defend them with beak and claw. Both are armed. One wields his knife to cut the apples into simple pieces, the other is watching to keep the snake at bay.

It is hard not to interpret the image in terms of the myth of the original sin. The children eat the apples, not only for nutrition, but also for insight. Maybe to reach the dream scene and the light. The childhood world, represented by the teddy bear, is abandoned. However, the world they are in is far from an original paradise. It seems rather as if Judgment Day has taken place. It seems a rendering of the biblical sense of sin, as in Genesis chapter 3: the fall of man by his revolt against God. Man himself will be like god, ie alive and forever: he will have both the tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil, but as he eats the fruit of the tree of knowledge, he must be driven out of the garden of Eden; that is to say, out of the unconscious, animal, vegetative, childish dimension. Perhaps the two boys are just looking for God.

Lise Jeppesen 2016